James Fuentes Gallery

YOUNG ELDER

James Fuentes is pleased to present Young Elder, featuring work by Andrea Carlson, Sonya Kelliher-Combs, Tyrrell Tapaha, and Nico Williams and curated by Natalie Ball and Zach Feuer. In an episode of Reservation Dogs, a TV series about the lives of Indigenous teenagers in rural Oklahoma, two influencers are invited to a community center for a Native American Reclamation and Decolonization Symposium. While rattling off self-righteous accolades, one of the speakers refers to himself as a “young elder”—an oxymoron that inspires a communal eye roll from the audience. The scene’s satire invites the question: what does it mean to express the wisdom of millennia through a contemporary practice? In Young Elder, four artists—emerging and mid-career—present recent work that references or applies Indigenous material and pictorial traditions as they are considered and carried on in the current day.

Through complex compositions that interlace Ojibwe and colonial narratives, ANDREA CARLSON’s practice questions what happens when the personal and impersonal intersect. With painting, drawing, and installation, she explores institutional critique from within the institution, mapping landscapes that expose unrecognized histories and re-envision worlds—making space for Indigenous communities to share their own narratives rather than have their experiences shared on their behalf. The Indifference of Fire, a twenty-four panel suite of ink, oil, acrylic, gouache, graphite, watercolor, and pen on paper, is a collage of four stacked landscapes with multiple horizon lines wherein the viewer is invited to wander through a continuous topography of symbols.

This work is an antidote to toxic and “bad medicine” narratives that stereotype Indigenous culture, layering references to plants and animals that symbolize healing and inhabit the thin margins where survival happens. One such detail is the white-throated sparrow, a bird with four chromosomal genders that ensures the continuation of its species. Compositionally, the work challenges colonial European traditions of landscape as a bordered space, for which each sheet of paper alludes to the treaties and deeds used to rupture and colonize Indigenous land. Thematically, the diverse flora and fauna challenge the fixed codes of Western allegory, encouraging metaphors that expand rather than contract meaning.

Working in mixed-media painting and sculpture, SONYA KELLIHER-COMBS explores the social, psychological, and environmental dimensions of her Alaskan heritage, considering how her identity impacts and influences the work she creates. The artist’s practice revisits and expands upon themes from her upbringing such as her community’s subsistence and utilitarian traditions—historically associated with women’s roles. Incorporating natural and artificial materials, Kelliher-Combs’ pieces implicate the viewer in acknowledging that disposable and built environments have endangered the natural state of the world, urging for a restored responsibility to the land we occupy and share.

Pink Slips is a sculpture series that references her culture’s custom of stretching animal skins. While some of her works incorporate real furs and hides, these pieces are synthetic paint “skins”—sculptures resembling hung fabric that are created by gradually layering coats of gel medium and acrylic polymer. Embossed with impressions of organic matter, Kelliher-Combs' presents these slips as the surface through which an individual mediates—and is scarred by—experience, addressing the physical and emotional abuse of women and children. Known as MMIW, the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Crisis, the slips touch on this movement which strives to recognize the untold histories of violence against Indigenous women.

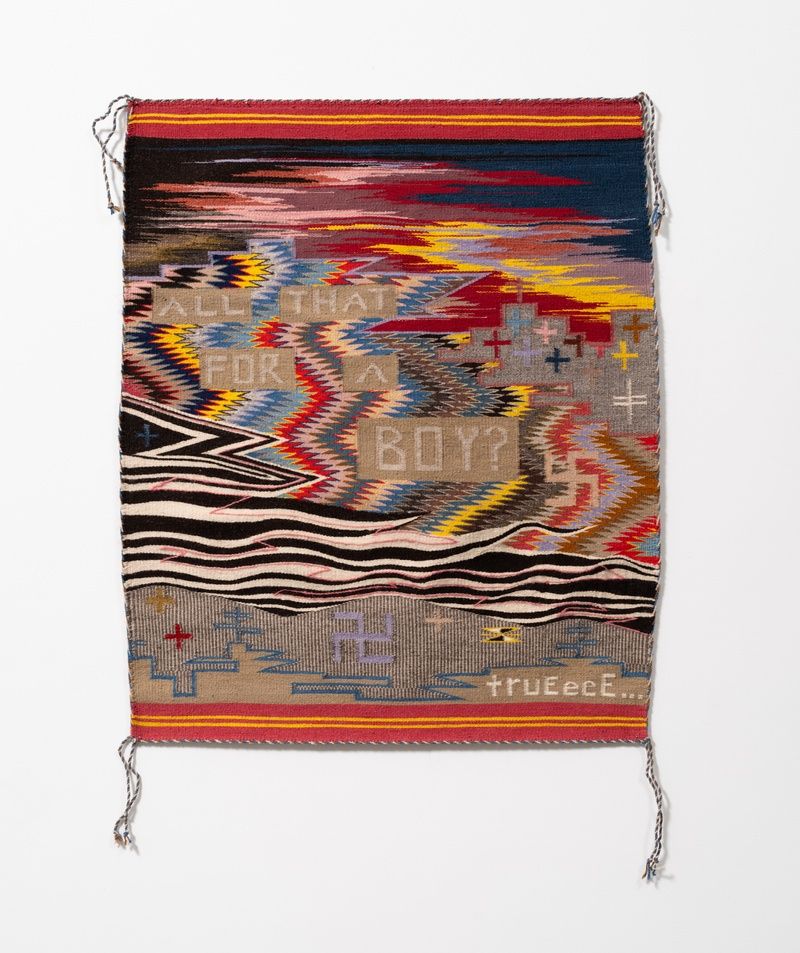

TYRRELL TAPAHA is a Diné weaver who preserves centuries-old techniques that have been passed down through their family for six generations. Throughout the Navajo Nation, weavings have always been a symbol of protection, livelihood, warmth, and utility. The artist considers what it means to be a weaver at this particular moment in history, adding a contemporary perspective to the legacy of their material. With a background in forestry and ecological restoration, they participate in each stage of the weaving process, a pastoral lifestyle carried on by very few people in their community. Throughout the year, Tapaha herds Navajo-Churro sheep, then shears, skirts, washes, and spins the wool. Each spool is dyed with vegetation from the surrounding Four Corners region, with hues extracted from fruits and plants like prickly pear, juniper, mountain mahogany, walnuts, and sagebrush.

Every work showcases Tapaha’s deep-dive into technique, intertwining Navajo and European weaving methods and imagery that range from landscapes to text messages—making space for experimentation and modern subject matter in a medium that is often reverent. Inviting vulnerability, one weaving is based on a collection of the artists’ notes and love letters. Other pieces play with humor, such as one depicting a cartoon sheep Tapaha’s relatives once printed on a family reunion t-shirt. Dimensions of the design are improvisational, testing colorful serrations, combining ancient patterns, and riffing on their family’s secret techniques. Tapaha understands their work as articulating a moment caught between past and future generations of weavers in their community—simultaneously preserving and inventing tradition.

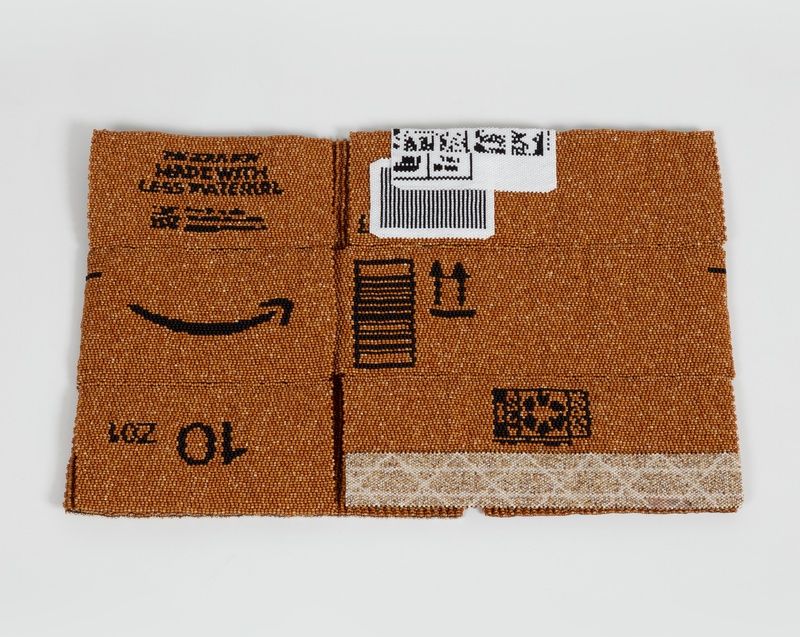

NICO WILLIAMS’ work begins with the found object. The artist is drawn to debris that he collects from his surrounding Hochelaga neighborhood in Tiohtià:ke/Montréal—materials coded with economic, political, and societal conditions. In the studio, he creates a digital rendering of the found object that is then used as a pattern for its recreation stringing together glass beads with thermally bonded weaving thread resulting in an intricate and sparkling soft sculpture. In this presentation, Williams creates a dialogue between four beaded sculptures: a flier for a supermarket, a strip of danger tape, an Amazon delivery box, and a wallet containing his Indigenous status card.

In the case of the coupon flier, Williams discovered the leaflet a few years ago when the Canadian government announced there would be a rise in food cost. Though on the surface the flier is comprised of mundane pantry items, Williams recognizes each as an emblem of the compounding factors of trade, commerce, agriculture, income, and access to essential resources. The replica of his Indigenous status card is folded into a leather wallet from which a beaded dollar bill emerges. For this piece, he also re-creates a Canadian ten-dollar bill from the 1970s—a period in which the currency was decorated with an illustration of the nuclear power refinery that was built in the artist’s home Aamjiwnaang Nation in Sarnia, Ontario. Drawn to beads both for their aesthetic qualities and their connections to Indigenous tradition, Williams celebrates beadwork as a culturally rich material through which he can create permanent documents of the lesser-known histories hidden within everyday ephemera.

Andrea Carlson (b. 1979) is a visual artist who maintains a studio practice in northern Minnesota and Chicago, Illinois. Carlson received an MFA from the Minneapolis College of Art and Design in 2005. Through painting and drawing, Carlson cites entangled cultural narratives and institutional authority relating to objects based on the merit of possession and display. Current research activities include land narratives, decolonization, and assimilation metaphors in film. Her work has been acquired by institutions such as the Whitney Museum of American Art, The Walker Art Center, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, the Denver Art Museum, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and the National Gallery of Canada, among others. Carlson was a recipient of the 2008 McKnight Fellow, a 2017 Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters and Sculptors grant recipient, a 2021 Chicago Artadia Award, and a 2022 United States Artists Fellowship. Carlson is a co-founder of the Center of Native Futures in Chicago.

Sonya Kelliher-Combs was raised in the Northwest Alaska community of Nome. She graduated with a BFA from the University of Alaska Fairbanks and MFA from Arizona State University. Through her mixed media painting and sculpture, Kelliher-Combs offers a chronicle of the ongoing struggle for self-definition and identity in the Alaskan context. Her combination of shared iconography with intensely personal imagery demonstrates the generative power that each vocabulary has over the other. Kelliher-Combs' process dialogues the relationship of her work to skin, the surface by which an individual is mediated in culture. Her work is included in the collections of the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Art, Anchorage Museum, Alaska State Museum, University of Alaska Museum of the North, Eiteljorg Museum, and The National Museum of the American Indian. Kelliher-Combs currently lives and works in Anchorage, Alaska. As an Alaska Native artist and advocate, she has served on the Alaska Native Arts Foundation Board, Alaska State Council on the Arts Visual Arts Advisory, and the Institute of American Indian and Alaska Native Arts Board.

Tyrrell Tapaha is a Dine weaver and fiber artist. While their predominant medium is Dine-style weaving, their work encompasses the intergenerational pastoral living handed down to them through their grandfather, great-grandmother, and relatives willing to teach. Their work acts as a tangible bank of feelings, memories, experiences, and a life that has been lived. This practice—that was once a hobby—is now intrinsically tied to their identity, a relationship that not only sustains their life force but is the powerhouse to many lifeways of their People. They weave with the intent of self-exploration, and hold themselves accountable to continuing an archaic artform that hasn’t changed in millennia. Every generation within their family has had its own experience with what this medium means to them. At times, it was a life-or-death scenario where weaving was the saving grace. In other settings, it’s what puts groceries on the table, buys books for school, and pays the rent. In a reciprocal cycle, Tapaha and their People give themselves to their weaving, and the weaving gives itself to them.

Nico Williams is a member of Aamjiwnaang First Nation (Anishinaabe), currently living and working in Tiohtià:ke/Montréal. Hisa multidisciplinary and often collaborative practice is centered around sculptural beadwork. Williams is an active member in the urban Indigenous Montréal Arts community and a member of the Contemporary Geometric Beadwork research team. He has taught workshops at The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the McCord Stewart Museum, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, and the University of Toronto. In 2021, he was awarded the prestigious Claudine and Stephen Bronfman Fellowship in Contemporary Art. His work has been shown internationally and across Canada, including at the Art Gallery of Hamilton (2023), the MacKenzie Art Gallery (2022), Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (2021), Musée des beaux-arts Montréal (2019), PHI Foundation for Contemporary Art (2023), and the recent group exhibition, Indian Theater: Native Performance, Art, and Self-Determination since 1969, at the Hessel Museum of Art.

Natalie Ball was born and raised in Portland, Oregon. She holds a Bachelor’s degree with a double major in Indigenous, Race & Ethnic Studies and Art from the University of Oregon, as well as Master’s degree with a focus on Indigenous contemporary art from Massey University, Aotearoa/New Zealand. Following her studies, Ball relocated to her ancestral Homelands in Southern Oregon/Northern California to raise her three children. In 2018, she earned an MFA in Painting & Printmaking from the Yale School of Art. Ball’s work has been exhibited nationally and internationally. She was the recipient of the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation’s Oregon Native Arts Fellowship in 2021, the Ford Family Foundation’s Hallie Ford Foundation Fellowship in 2020, the Joan Mitchell Painters & Sculptors Grant in 2020, the Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant in 2019, and the Seattle Art Museum’s Betty Bowen Award in 2018. Today she is an elected official serving on the Klamath Tribes Tribal Council.

Zach Feuer, along with Becky Gochman, is a co-founder of Forge Project. Forge is a Native-led initiative focused on decolonial education, Indigenous art, and supporting Native leaders in culture, food security, and land justice. Previously, Feuer was director of the sculpture park at Art Omi in Ghent, New York, before which he owned and operated various galleries in New York City, Los Angeles, and Hudson. He is a co-founder of New Art Dealers Alliance and is the director of the Gochman Family Collection.

Nico Williams

Special Delivery, 2023

10/0 glass beads

10 × 31 ½ inches

Works

Tyrrell Tapaha

Sonny Boi Summer, 2023

Handspun and vegetal dyed Navajo-Churro, mohair, and alpaca tapestry

40 3/4 × 34 inches

Tyrrell Tapaha

Better Don't pt. I, 2023

Hand spun Navajo churro and alpaca yarn, vegetable dyed tapestry

16 × 12 inches

Tyrrell Tapaha

Better Don't pt. III, 2023

Handspun and vegetal dyed Navajo-Churro, mohair, and alpaca tapestry

17 ½ × 13 inches

Tyrrell Tapaha

Better Don't pt. II, 2023

Hand spun Navajo churro and alpaca yarn, vegetable dyed tapestry

16 × 12 ½ inches