James Fuentes Gallery

Purvis Young

Purvis Young

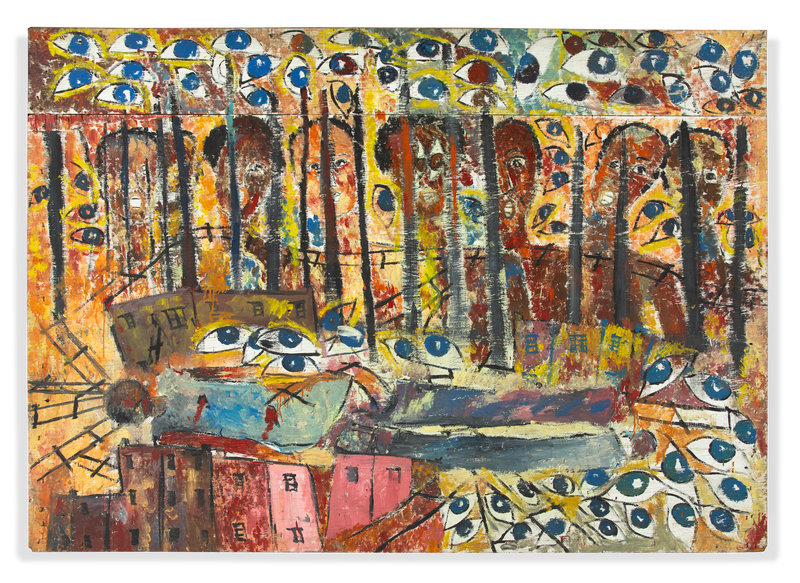

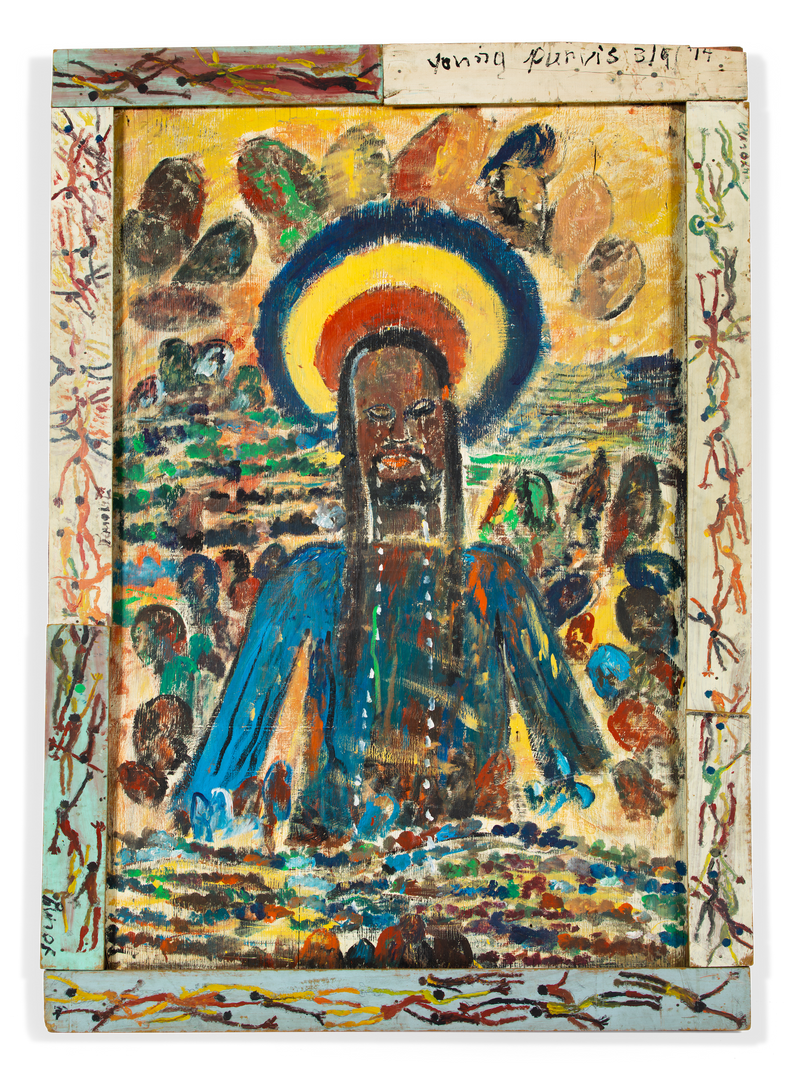

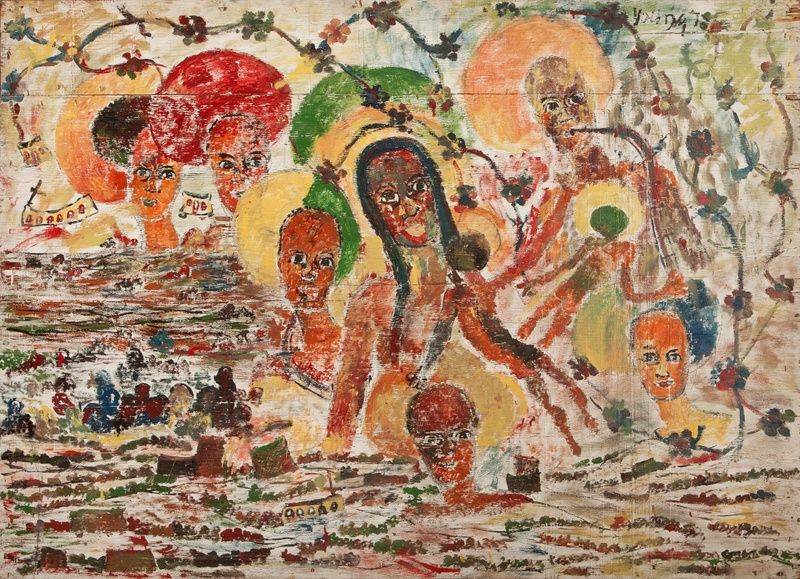

Young was self-taught, producing a remarkable number of works over his lifetime that convey rich scenes—at once pictorial and spiritual—of his life spent in the inner-city Miami neighborhood of Overtown. Informed by an early practice of drawing from life, Young began making paintings in the 1960s. Blending techniques of painting, drawing, and collage, Young collected discarded materials found on the streets and in abandoned buildings across his locale to incorporate as the surfaces for his work. Elements of action, figuration, and storytelling are laid over a series of structural devices, activating the ways in which the found materials onto which Young painted would serve to frame the images placed upon them. While some of these panels are smoother or more straightforward in proportion, others approach a mode of assemblage that reflect the variable and multi-layered narratives found across the artist’s work. The materiality of Young’s paintings reflects the artist’s own relationship to architecture, place, and time in Overtown. This sense of site-specificity is translated when encountering the works in person, whereby the panels offer a certain reconstruction of the environments from which they once came.

Young’s use of repurposed materials also speaks to the artist’s long-running ecological concerns, which are often expressed in the imagery of his works. At the beginning of his life, Young was witness to a time of political and social upheaval, including the civil rights movement as well the Vietnam war and the spirit of mass protest against it. Coming into adulthood, he was of aware of the large outdoor murals created by artists in Detroit and Chicago. Young began attaching his own panels to the front of abandoned buildings, doubling as a kind of material return for the work itself. Around 1972, Young began his large-scale outdoor project known at Goodbread Alley, which he filled with innumerable paintings over time on a rotational basis. Coupled with Young’s choice of this particular mode of presentation for his works, he considered the paintings to be fine art, and would most often sign his name on the front of the image. The majority of Young’s works were not titled and often undated, aside from those later applied by a third party seeking to catalogue or categorize the paintings. For this reason, works in across this exhibition have purposefully been left untitled—as have the four parts of the presentation. Without the artist’s input today, this exhibition seeks to offer a view beyond such categorization, presenting new points of entry to his work.

PART ONE is presented November 1–December 1, 2020 at jamesfuentes.online, consisting of a series of works that range in subject—depicting cities, angels, and figures playing games, riding horses, celebrating, or in procession. Many of these works share one common element: eyes that float across the paintings. Young believed that green and blue eyes were watching over him at all times, and likely controlling the world at large. Here, the eyes that seemed to have followed the artist as he lived and worked now stare back upon the viewer, enlarged and crammed between objects, multiplying en masse across the panel, or hiding between and within structural details. Upon each ground, Young presented highly densely populated scenes that show bodies in states of movement, floating, and reclining. In many works Young conveys scenes of procession and transcendence, found in funeral marches, riots, and in figures traversing train tracks or ascending to the heavens. In some, the red sun appears, considered to be an omen of death, either material or metaphysical. In others a large, saintly body is carried horizontally by many smaller figures. These paintings point to the intersection of larger themes in Young’s work, where spiritual elements factor into scenes of community mourning and celebration.

PART TWO in presented from November 11–December 6 at the gallery’s location at 55 Delancey St. This selection presents a complex group of works that together speak to the distinct iconography as well as religious narratives that run through Young’s works. Figures and faces are surrounded by large halos, often depicted against detailed landscapes that prompt drastic shifts in scale between people and place. In some works, the subject is shown with tears down their face. In others, the subject’s mouth is open as if singing, while another plays the saxophone, emphasizing the spiritual importance of music within Young’s life and work. In many of these, works Young depicts vibrant cityscapes at a perspective further removed from the subject. These densely populated scenes do not resemble the artist’s own neighborhood. Instead they present imagined, apocalyptic scenes wherein wild horses run through the city, a hanging takes place from a building, and innumerable figures move in between. Young visually describes the city as a site of judgment or reckoning, and at the same time populates these scenes with as many stars as people; encapsulating the circle of life.

From 2018–19 Young was featured in a solo exhibition at the Rubell Museum in Miami. His work is included in the collections of the American Folk Art Museum, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian’s Corcoran Gallery of Art, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and the High Museum of Art, among others.