James Fuentes Gallery

Kikuo Saito

Kikuo Saito

Kikuo Saito (1939–2016) was born in Tokyo and moved to New York City in 1966 at the age of 26, curious about the city’s burgeoning artistic movements. Saito had began painting a decade prior, building a steady understanding of traditional Japanese arts alongside contemporary movements such as the Gutai Group, while working for three years in the studio of established traditional painter Sensei Itoh. Landing in San Francisco, Saito traveled to New York by bus, visiting the country’s museums and witnessing its variable and remarkable landscape, confronted by the city’s own topography of signs upon arrival.

During his first decade in New York, Saito worked between painting and theater. In many senses, he considered much of life as a performance. For his wordless theater pieces, Saito incorporated ephemeral, nontraditional materials like water and earth with elements of music, movement, and light, drawing inspiration in part from the performance traditions of Kabuki, Noh, and Butoh. These were collaborative works, in which Saito directed dancers and actors while creating stage costumes, sculptural elements, and using his abstract paintings as backdrops. Saito’s theater was well-received and in turn led to collaborations (and further travel) with Robert Wilson, Jerome Robbins, Eva Maier, and Peter Brook. In 1979 he decided to devote his attention entirely to painting, preferring the serene isolation of the studio, where he could physically manipulate paint across ground, over the complex, multi-disciplinary approach behind his theater pieces. This break lasted 17 years—until his brief return to theater with the presentation of Toy Garden in 1996, in which he imagined the missing half of Vittore Carpaccio's painting Two Venetian Ladies (c. 1490)—and he remained dedicated to painting throughout his life. The selected works on view mark the breadth of the artist’s career from the late 1970s onwards.

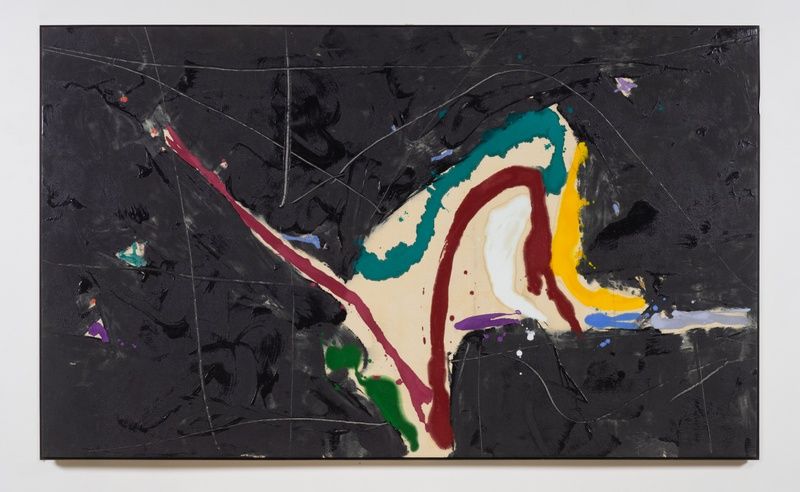

Saito attended to a number of concerns throughout his decades of painting, which he would continually reference and revisit, forming feedback loops across time. At the core of his work is the early interplay between theater and painting—informing the body’s movement of paint across the surface; switching status between backdrop and immediate surface; implying observation and delivering sensation. Early on, he moved from using acrylic to oil paint (although returned to it much later). The quick run of acrylic required that the canvas be fixed to the floor and therefore rapidly danced across, whereas the slowness of oil afford a vertical orientation and more direct interaction between the hand, wrist, and surface. Relatedly, the translucent, changeable quality of oil allowed a deeper integration between the paint and its ground, rather than necessarily consigning the canvas as background. Through his intensive commitment to painting, Saito was able to render expression more explicit, permanent, and exclusive.

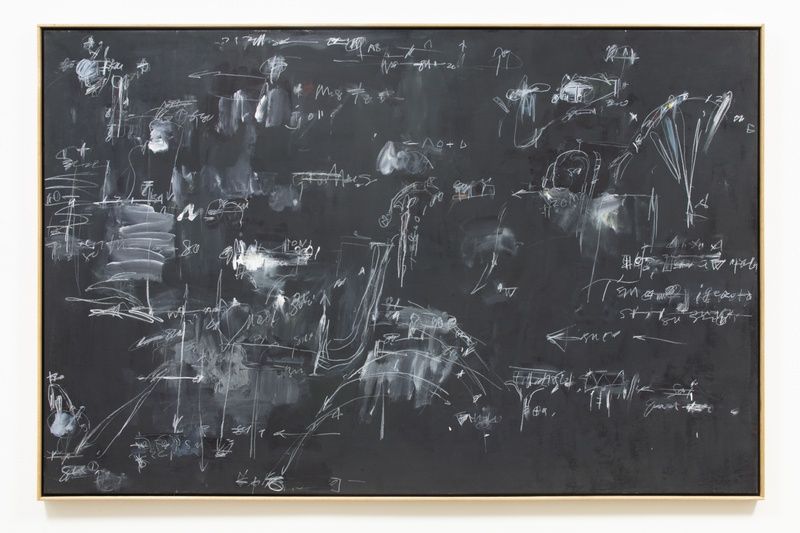

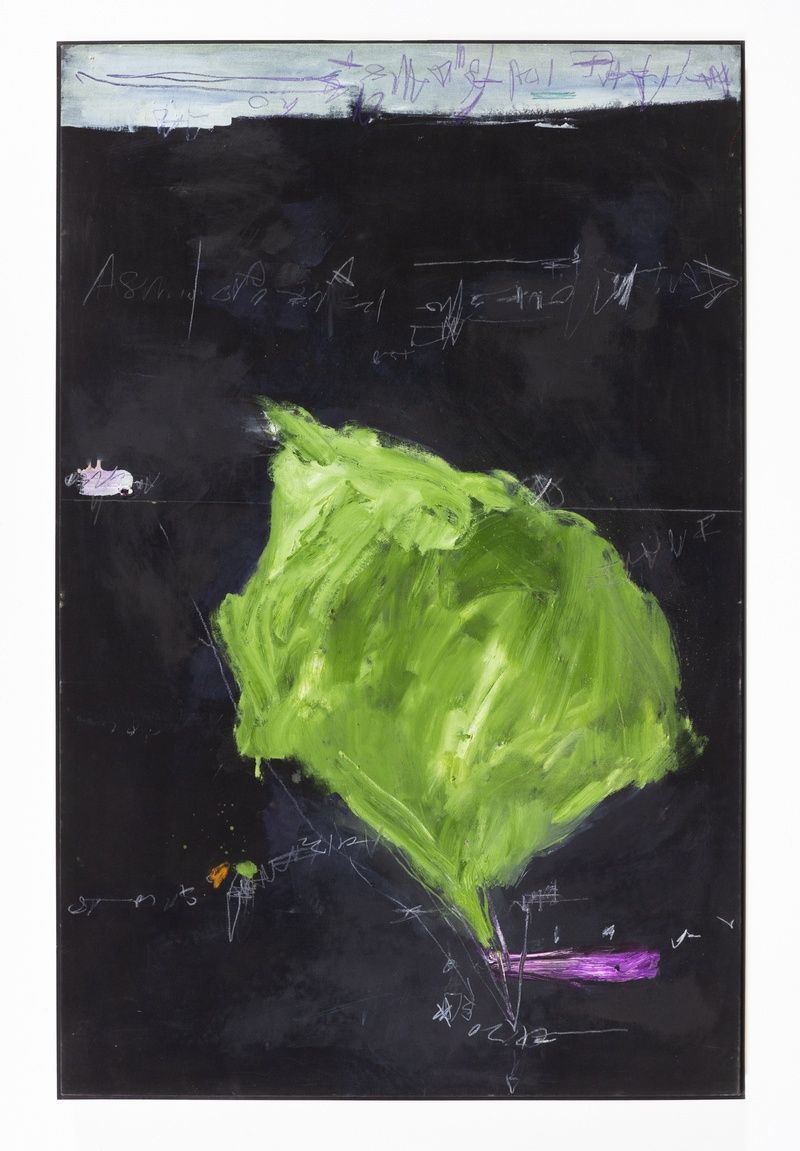

For Saito, much like his mysterious theater, painting relied on the explicit relationships of color and light, alluding to examinations in nature and daily life rather than offering the literal or pictorial. He approached language the same. Having arrived to the New York with minimal knowledge of English and its alphabet seen across the city’s signage, Saito delivers a visual sense of language in his paintings: to be felt rather than read. Through this process, Saito internalized not just the foreign but the formal, and conveyed the double-nature of signs. By approaching the near-infinite possibilities of combining letters, yet eliding actual words or readable sentences, meaning might instead be found in form and color. In the artist’s approach to drawing as well, the shift between drawing and painting undulates—from broad sweeps to thin lines, scratched-in marks, impromptu scribbles, arrows, seemingly abstracted calligraphy, to floating letters that act like objects rather than forming legible words or sentences. Altogether, the works offer notations that change pace and direction, just as color reacts to color, and (later) language becomes form; so as to necessarily involve—and even instruct—the one looking into or at them.

In order to approach the sheer depth of Saito’s persistent investigations, the works on view carry the commonality of the color black. In his earlier works, carrying the influence of Color Field painting, black washes across the surface while brilliant color peaks through and makes space against unfinished canvas. Next, colors would sit alongside or on top of one another, surrounded by a series of undecipherable marks. In another, color vacates so that light and dark are more explicitly directed by a dense overlay of drawn elements, resembling a chalkboard. With these marks Saito referenced choreographic notation, to be potentially read as a map for responsive movement. Later, color and tone occur rapidly all over, possibly implying the shimmering reflection across water or dappled light, becoming lyrical. In some works, windows of light open at the edges and corners of the canvas. In others, elements of the alphabet enter the frame, adapting language and letters into compositional forms. Over time, questions of form, color, balance, and movement were at once queries of light and darkness, too.

Saito’s longstanding interest in choreographic expression and theory is evident throughout his immense body of work. For the artist, orientation was often mutable, yet he approached scale and proportion with utmost precision (he would paint on canvas and then edit down its size to the precision of millimeters). This level of sensitivity is evidenced further by the artist’s repeat revisitations. Across his black paintings, Saito presents precisely the opposite of the expected ground (of a blank canvas)—at the same time upending expectations of meaning (through language and representation). Through these opposite values, he was intent on drawing focus to color itself, making it new. Saito’s returns offered a continued process of exchange for these concerns within his work, as did his external movement and travels within the world.

KIKUO SAITO was an artist-in-residence at Duke University, a visiting professor at Musashino Art University in Tokyo, and a painting instructor at the Art Students League of New York. His work has been presented in exhibitions at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Portland Art Museum, Loretta Howard Gallery, Andre Emmerich Gallery, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, Salander-O’Reily Galleries, Leslie Feely Gallery, Jill Newhouse Gallery, and Octavia Gallery. His work is featured in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum, the Aldrich Contemporary Museum, the Nasher Museum of Art, and numerous corporate and private collections. The nonprofit organization and interdisciplinary art space KinoSaito will open in Verplanck, New York later this year. A publication on Saito’s work by James Fuentes is forthcoming.