James Fuentes Gallery

GIANT WOMEN ON NEW YORK

Opening reception: Friday, March 21, 6-8pm

Giant Women on New York brings together a group of artist who became peers in New York City during the late 1960s and early ‘70s. The exhibition offers a brief window into a politically charged and art historically important moment in which they advanced the field of figurative painting through their respective practices, and engaged in activist organizing around this shared artistic commitment.

As members of the Alliance of Figurative Artists, Alice Neel, Juanita McNeely, Joan Semmel, and Anita Steckel were part of a network that championed figuration at a time when Abstract Expressionism as well as Conceptual Minimalism dictated innovation in local and national discourses. Insisting on the figure as subject, this group of peers instead pushed the possibilities of figuration to absorb their experiences, observations, sensations, and improvisations.

In parallel, many of these artists shared membership in other significant activist networks and gallery co-ops, including the Fight Censorship Group (founded by Steckel in 1973), Women Artists in Revolution (W.A.R.), and the Prince Street Gallery—alongside peers Nancy Spero, Louise Bourgeois, and Martha Edelheit, and many others. Against this backdrop, and in light of their five decades of work since, this exhibition seeks to assert each artist’s autonomous approach to the figure starting in the 1970s, resisting categorization, oppression, and domination to independently establish distinctly recognizable oeuvres from that moment onward.

Organized by Laura Brown.

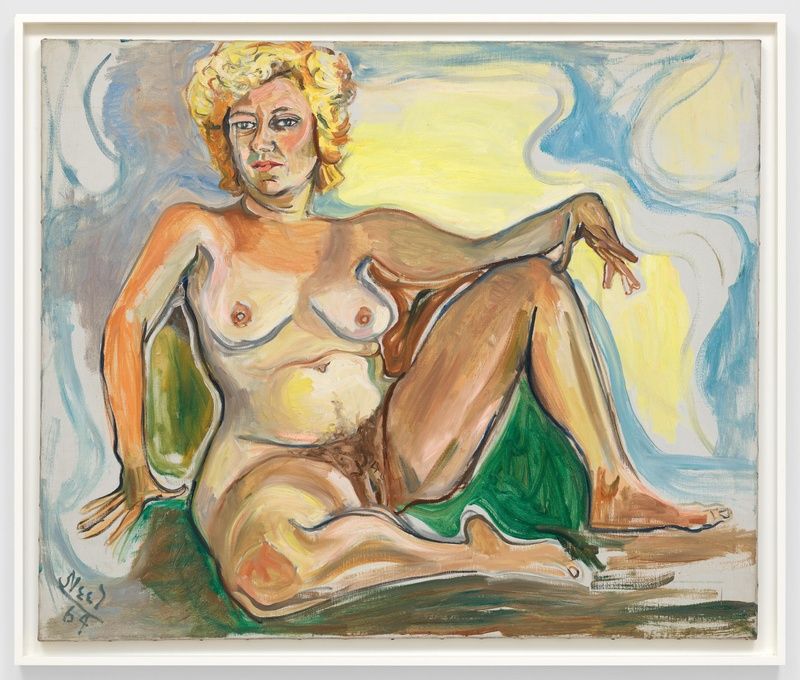

Alice Neel (1900–1984) is known for her daringly honest and humanist approach to the figure. As the American avant-garde of the 1940s and ‘50s renounced figuration, Neel reaffirmed her signature approach to the human body. Working from life and memory, she painted writers, poets, artists, activists, family, friends, and others around her with unfazed accuracy, honesty, and compassion. Throughout her career, Neel was attracted to unusual characters whose physical attributes and personalities were intriguing and visually appealing to her. Her strong power of observation and unique ability to empathize is reflected in her psychologically charged portraiture, which captures the individuality of her sitters in an unforgiving yet tender manner. Calling herself a "collector of souls," Neel is acclaimed for not only capturing the truth of the individual, but also reflecting the political and social milieu in which she lived. Her reexamination of the human body paralleled the cultural upheaval of the sexual revolution and women's movement: her work challenged the Western artistic tradition that regarded a woman's proper place in the arts as sitter or muse.

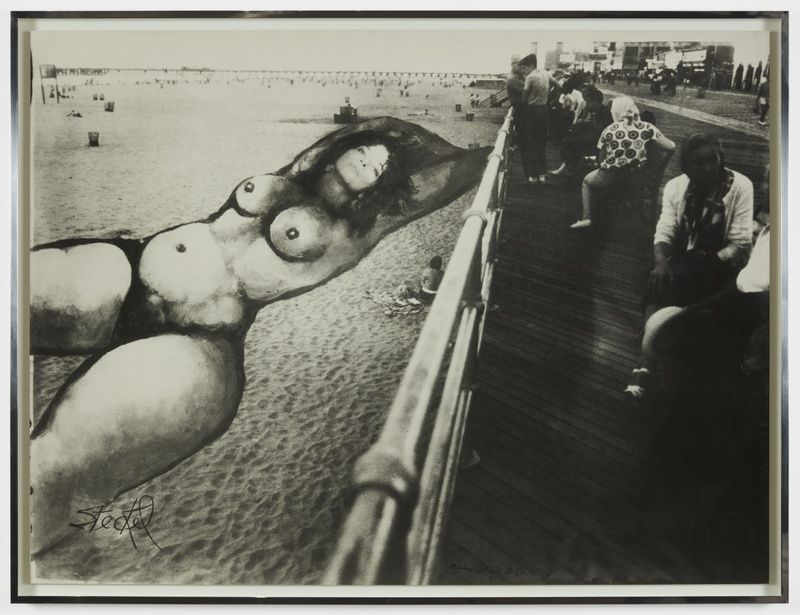

Anita Steckel (1930–2012) experimented liberally across mediums of pencil, oil, silkscreen, Xerox, assemblage sculpture, and poetry to develop an ongoing critique of the sexism in Western art history and the prudishness of postwar American society. An unapologetic New Yorker, feminist, and satirist, Steckel reflected on women’s experience of public space and modernity in the urban capital of the twentieth century. Her best-known works give form to scenes of unconscious pleasure and play, interweaving subliminal landscapes of desire with visible architectural realms. While several critics condemned her work as pornographic, Steckel used erotic imagery to illustrate heterosexual female desire and provide her own interpretation of previous art featuring nudity, especially art by men featuring women. In her Giant Woman series, a nude female figure confidently treks through New York City. In response to demands to cancel her 1972 solo exhibition, The Feminist Art of Sexual Politics at Rockland Community College, on the grounds of obscenity, Steckel formed the Fight Censorship Group, aimed at protesting institutional double standards. The exhibition’s title refers to Steckel's work made that same year.

Joan Semmel (b. 1932) has centered her practice around representations of the body from the female perspective. Trained as an Abstract Expressionist in the 1950s, Semmel began her painting career in Spain and South America. Returning to New York in the early 1970s, she turned toward figurative painting, constructing compositions in response to censorship, popular culture, and concerns around representation. Her practice traces the transformation that women’s sexuality has seen in the last century, and emphasizes the possibility for female autonomy through the body. The Overlays series (1992–96), combines conceptual and formal concerns that echo many of Semmel’s previous investigations. For this body of work, she used pre-existing paintings from her Erotic Series (1972) as a background for gestural images of nude, middle-aged female bodies taken from her prior Locker-Room paintings (1988º91). These works represent a fertile moment of formal experimentation as Semmel began exploring color and transparencies. Writing about this series, she observes, “both non-naturalistic color and linear overlays of complementary or contrasting images, again recall abstract elements, but also provoke a suggestion of time, motion, or memory.”

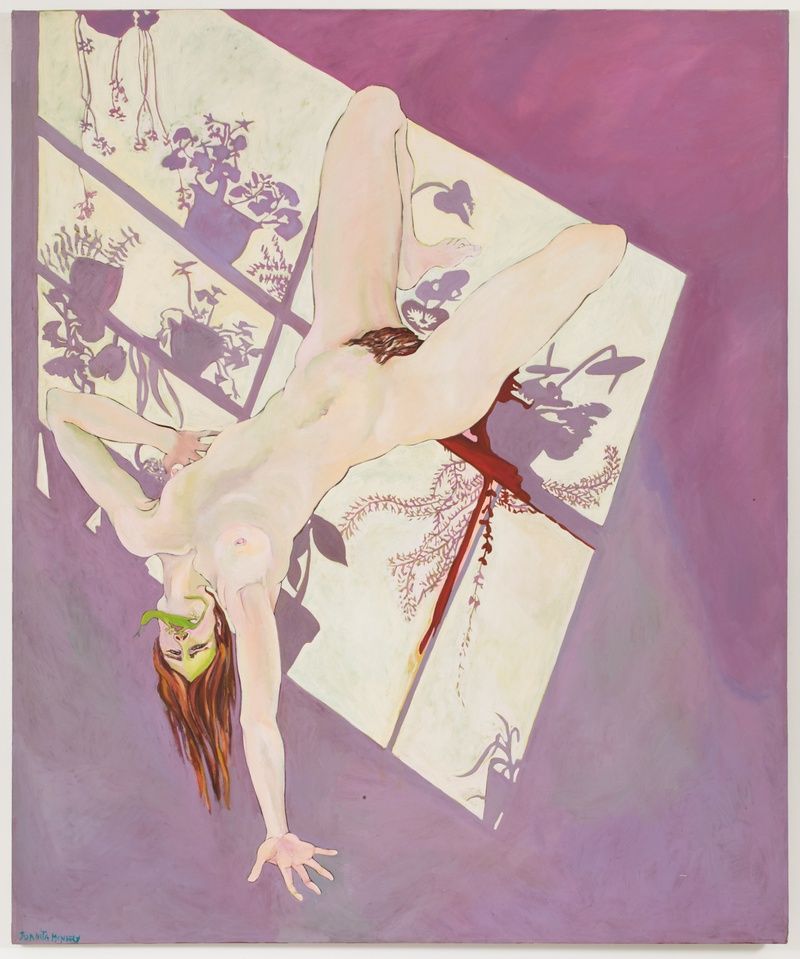

Juanita McNeely (1936–2023) conveyed the extreme physicality and movement of the human figure, informed by her close observation of others as well as her personal experiences of sexism, abortion, illness, and disability. Over time, McNeely developed a powerful visual vocabulary that focused on the human condition depicted in radiant color ranges filled with lightness and shadow—driven by the need to “make the ugly and the terrible beautiful for myself.” Her figurative work brazenly defied the conventions of art history, approaching the human form as a source of power, emotion, movement, and rupture. In time, the central figure has become more clearly identifiable as the artist herself; and the violence and extreme frustration of facing external, often male, control over her body deeply informed her work. Her figures are often contorted, suspended in mid-air, and directly interfacing with the picture frame itself, unconstrained by gravity and resisting confinement.

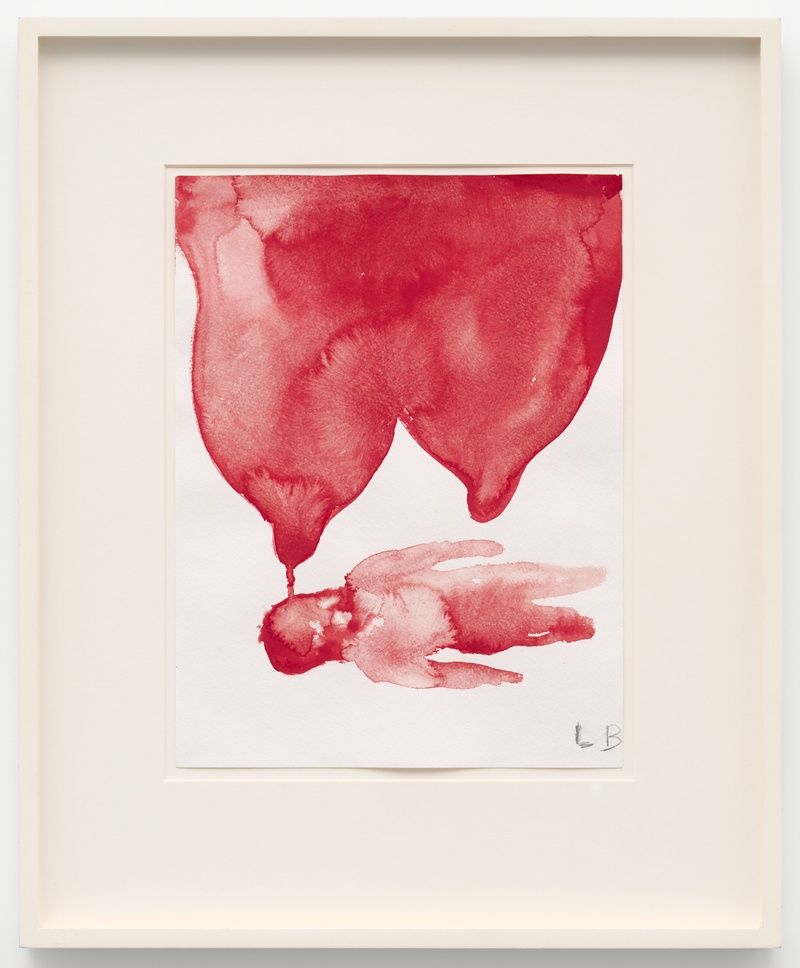

Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010) is celebrated for her creative process fueled by an introspective reality, often rooted in cathartic re-visitations of early childhood trauma and frank examinations of female sexuality. Articulated by recurrent motifs (including body parts, houses, and spiders), personal symbolism, and psychological release, the conceptual and stylistic complexity of Bourgeois’s oeuvre plays upon the powers of association, memory, fantasy, and fear. Bourgeois’s work is inextricably entwined with her life and experiences, fathoming the depths of emotion and psychology in a distinctive symbolic visual code that enmeshes the complexities of the human experience and individual introspection. Made when the artist was in her late nineties, The Feeding (2007) presses at the “realistic” depiction of the human body, while exploring a vast range of physical and psychological aspects of being both mother and child. Ultimately, for Bourgeois the dynamics of providing care for another was fraught with overarching feelings of responsibility, vulnerability, and anxiety, as much when she was a child as it was at the age of ninety-five.

Martha Edelheit (b. 1931) confronts dominant art historical paradigms in her work, foregrounding a female gaze and desire. Known for eroticism, her lush and vivid work is at once critical, sensual, and humorous. She is known for both her frank depictions of sexuality and her insistence on their place within an art historical tradition and society. By the early 1970s, Edelheit began to work with the combination of nude figures, photographs, and memory. She was interested in “montage”—combining elements and even figures who didn’t necessarily pose together. In her monumental paintings of nude women and men situated on luscious drapery or montaged into familiar locations around New York City, she sought to explore certain how symbols could become signifiers of the inner life of her subjects, as well as the urban experience. The artist’s output from this period reflects her abiding love of art history and her reimagining of the discipline that was largely created by men, for men.

Nancy Spero (1926–2009) made the female experience central to her art and challenged aesthetic and political conventions. Her lexicon was derived from an immersion in the history of images, notably from Egypt, classical antiquity, pre-history, and contemporary news media. She combined, fractured, and repurposed found imagery and adopted text to comment on contemporary and historical events. With raw intensity, Spero executed works on paper and installations that persist as unapologetic statements against the pervasive abuse of power, Western privilege, and male dominance—consistently seeking to meet what she considered to be the societal obligations of the artist. In her War series (1966–69) Spero personified weapons and wartime horrors in response to the conflict in Vietnam. The work collapses depictions of a weapon and the body that has been destroyed by it, highlighting the devastation caused by tools of warfare. Spero was fiercely committed to the representation of women in art and portrayed them as both victims and as sources of violence. The strokes of red extending from the heads in works like Bomb, Dove and Victims (1967) can be read as tongues as well as blood, giving form to Spero’s rebelliousness.

* The exhibition title refers to Anita Steckel's 1973 work on view.

James Fuentes would like to thank the collaborators who helped make this project possible: David Zwirner, Alexander Gray Associates, John Cheim, Bueno & Co, Eric Firestone, and Galerie LeLong & Co.

Works

Anita Steckel

Giant Women on New York (Coney Island), 1973

Silver gelatin print

35 ½ × 47 3/4 inches

Juanita McNeely

Window Shadow: Chameleon on Woman's Face, 1975

Oil on canvas

84 × 69 inches

Louise Bourgeois

The Feeding, 2007

Gouache on paper

14 5/8 × 11 inches

Alice Neel

Ruth Nude, 1964

Oil on canvas

43 3/8 × 51 3/8 × 1 3/4 inches (framed)